|

| Via Wikipedia, a map of Pennsylvania with counties labeled. |

Greetings from the center of Presidential

politics, rural Pennsylvania.

Most political observers know that Donald

Trump was the first Republican since 1988 to carry the Keystone State, but fewer

realize that Trump’s victory broke an even longer-standing pattern. Pennsylvania was once one of the most

Republican states in the Union, voting for the GOP in every election between

the Civil War and New Deal (except 1912, when it went for Theodore Roosevelt’s

third-party bid), even sticking with Herbert Hoover in 1932. Franklin Roosevelt carried the state the

other three times he ran, but by smaller margins than he won the national

popular vote, and Pennsylvania went for Thomas Dewey over Harry Truman in 1948. In 1952, however, Pennsylvania began a

pattern of being slightly more Democratic than the nation as a whole and stuck

to it until 2012.

(The source for this data and all other election data in this series is Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections at https://uselectionatlas.org/.)

As you can see, in every election from 1952

until 2012, Pennsylvania was more Democratic than the national popular vote,

but by six percentage points or less in every year except the 1964 and 1984

landslides. The 2016 election broke this

pattern, as Donald Trump carried Pennsylvania while losing the popular vote

nationwide.

This consistency masked a number of changes

going on within the state. Western

Pennsylvania, once heavily Democratic, became solidly Republican outside the

city of Pittsburgh. The Philadelphia

suburbs, once a Republican stronghold, have become more Democratic. In the central part of the state, Republicans

have increased their margins in rural areas while losing ground in some cities,

such as State College, Harrisburg, and Lancaster. A number of more blue-collar cities, such as

Erie and Scranton, seemed to be getting more Democratic, but swung toward

Donald Trump in 2016.

Pennsylvania Regions

The most fundamental division in

Pennsylvania’s geography runs along the Blue Mountain, at the eastern edge of

the Appalachians. It crosses the

Mason-Dixon line almost halfway across the state’s southern border, near

Chambersburg, then runs north of Carlisle, Harrisburg, Lebanon, Reading, and

Allentown, roughly following the path of Interstates 81 and 78. Pike and Monroe counties, in the Poconos, are

north of the Blue Mountain, but their proximity to the New York metropolitan

area makes their demographics more aligned with the area to their south.

The area south and east of the Blue

Mountain is mostly part of the Piedmont, the area of rolling hills stretching

from New York City to Alabama. It tends

to align with the Northeastern cities, mostly with Philadelphia, but in some

areas with New York or the Baltimore-Washington region. Outside of already densely packed

Philadelphia and some of its suburbs, its population has grown at an impressive

rate for a northern state. It is

relatively affluent. Politically, it has

shifted to the Democrats (especially in the areas around Harrisburg, Lancaster,

and the Philadelphia suburbs), but Republican margins have been holding, or

even increasing, in the areas around York and Reading (rhymes with “wedding”).

The area north and west of the Blue

Mountain is the stereotypical Pennsylvania of coal mines and steel mills. It tends to identify with the Midwest or

Appalachia. It is not as wealthy as

south-central or southeastern Pennsylvania, and, outside of State College and

some of the Pittsburgh suburbs, its population is either declining or growing

slowly. It is either part of the

Appalachian Mountains or the Allegheny Plateau, the easternmost part of the

Mississippi River basin. Politically,

the Democrats used to have a great deal of support here, but it began turning

toward the Republicans around the turn of the millennium (there are counties

here that voted for Walter Mondale, John McCain, and Mitt Romney), a trend

which has accelerated with the rise of Donald Trump.

|

| Population growth by county, 2000-10 (Source: U.S. Census Bureau) |

|

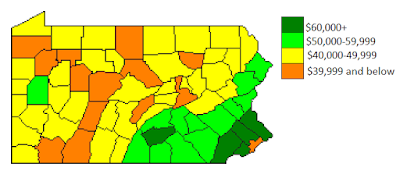

| Median household income by county, 2010 (Source: U.S. Census Bureau) |

Another way to split Pennsylvania is into

four basic regions, one entirely east of the Blue Mountain, one entirely west,

and two straddling it. These regions

are:

- Bidenland, a term coined by Brandon Finnigan of Decision Desk HQ. This region consists of several small, blue-collar cities (Reading, Allentown, Bethlehem, Scranton, and Wilkes-Barre) in northeastern and east-central Pennsylvania. The Blue Mountain divides it between the anthracite coal region, stretching from Scranton to Schuylkill County, and a string of exurban areas from Reading to the Poconos. It tends to be evenly divided in elections, but swung to Trump in 2016.

- Central PA, the area James Carville had in mind when he described Pennsylvania as “Philadelphia and Pittsburgh with Alabama in between”. This is the state’s Republican stronghold, and its presence is what keeps Pennsylvania in play for them. The Blue Mountain divides it between the growing area around Harrisburg, Lancaster, and York, and the more thinly populated Appalachian area.

- SEPA, or Philadelphia and its “collar counties” (Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery). This is the smallest region by land area, but the largest by population. In the past, the Republican suburbs balanced the Democratic city, but recently, both have become Democratic strongholds. Since the mid-20th century, it has held steady at just under a third of the state’s population.

- Western PA, the most stereotypically “rust belt” region. It contains the Pittsburgh metro area, as well as Erie and several smaller, blue-collar cities such as Johnstown and New Castle. Once heavily Democratic, Republicans have made impressive gains here, but its shrinking population is making it less of an asset in statewide elections.

I’ll look at each of these regions in

detail, including the sub-regions and trends within each, in subsequent posts. For now, here is a look at how the four

regions voted, both in absolute terms and relative to the national popular vote,

showing the trends I’ve mentioned above:

Below is the population of each region,

both in absolute terms and as a percentage of the state:

As you can see, Bidenland declined slightly

before growing again, as the suburban areas around Reading, the Lehigh Valley,

and the Poconos grew, while the southeast has been fairly steady at just under

one-third of the state’s population.

Central Pennsylvania has grown steadily, while Western Pennsylvania has

declined.

No comments:

Post a Comment