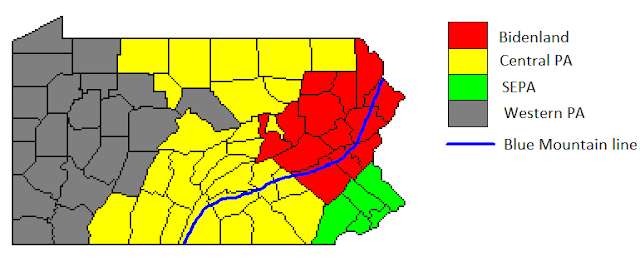

Finally,

we come to western Pennsylvania, the home of Pennsylvania’s second-largest

city, Pittsburgh, as well as a number of smaller cities (such as Erie, Johnstown,

and New Castle) and suburban and rural areas. Although it has steadily lost population since

the 1960s, its stark turn to the Republicans has been a defining feature of

Pennsylvania politics since the turn of the millennium.

Setting

aside Pittsburgh for now, the most defining feature of western Pennsylvania

might be its old industrial and coal mining towns and small cities. This area wraps and winds throughout the

area. Johnstown might be its most iconic

city and is the home of its namesake, longtime Congressman John Murtha. From there, Murthaland goes northward

throughout Cambria County into Elk County, a German Catholic stronghold, and

Clinton County, and west into Indiana, Armstrong, and northern Westmoreland

counties. It includes Fayette and Greene

counties in the state’s southwest corner and goes from there northward into the

Monongahela (or, as locals call it, the “Mon”) and Beaver valleys. Murthaland stretches as far north as the

cities of New Castle and Sharon, directly across the Ohio border from Youngstown.

While

Congressman Murtha first came to national attention in 2005 and 2006, when he

became one of the leading members of Congress opposing the war in Iraq (a

stance given more credibility because of his service as a Marine in Vietnam),

he had been a fixture in western Pennsylvania politics since being elected to

Congress in 1974. He had risen to

prominence in setting defense policy, a position he used to steer as much

spending as he could to his district, and had survived several rounds of

redistricting while the area’s chronic population loss meant its districts were

frequently chopped up. By 2001, the

Republican state legislature’s desire to preserve Murtha’s clout while making

surrounding districts friendlier to Republicans led them to pack his district

with as many Democratic-leaning industrial towns as they could, creating a

gerrymander that wrapped from the southwest corner and Mon Valley to Johnstown,

then doubled back, plucking the towns of Indiana and Latrobe from their

surroundings, before ending in the northeastern corner of Allegheny County.

By

this time, though, the fundamentals of Murthaland were changing. Although Murtha never had any trouble being

re-elected before his death in February 2010, and his chief of staff, Mark

Critz, held the district in the 2010 tea party wave, the Twelfth District was

the only district in the country that voted for both John Kerry in 2004 and

John McCain in 2008. (Perhaps it just

really likes Vietnam veterans named John.)

Even before the 2010 wave, Republicans began making inroads in the

area’s state legislative delegation.

The

more rural areas of northwestern Pennsylvania, as well as some of the suburbs

of Pittsburgh, were Republican strongholds even when western Pennsylvania was

heavily Democratic: you might call them Hipster Republicans. Northwestern Pennsylvania was America’s first

oil patch; it was here that the first modern oil well was dug around the time

of the Civil War, and that Standard Oil got its start. The area still produces some oil, but has

been eclipsed by the Great Plains, Gulf Coast, and Alaska. Politically, they’re joined by much of the

Allegheny County suburbs around Pittsburgh, as well as parts of neighboring Washington

and Westmoreland counties. Butler

County, where Rick Santorum grew up and where current Congressman Mike Kelly

has his base, acts as a bridge between the two areas. Suburban Pittsburgh has traditionally been a

strong base for statewide elected Republicans.

The last four Republicans elected governor were from western

Pennsylvania. Two of them (Richard

Thornburgh, who served from 1979-87, and Tom Corbett, who served from 2011-15) came

from Allegheny County, as did Senator John Heinz, who served from 1977 until

his death in plane crash in 1991. Heinz

won his 1988 re-election effort by a 66-32% margin, the biggest landslide for a

Pennsylvania Republican in modern times, and carried every county in western

Pennsylvania even as Michael Dukakis won the region.

As

with affluent suburban areas throughout the country, though, Democrats are

making inroads into suburban Pittsburgh, particularly in northern and

south-central Allegheny County, spilling into part of southern Butler County. This came to the nation’s attention, when,

after near-misses in Wichita, the entire state of Montana, rural South

Carolina, and the Atlanta suburbs, they won a special election for a

Republican-held house seat here in March 2018.

In honor of the winner, Conor Lamb, who won the general election last

year (in a reconfigured district due to a court order), I’m calling this area Lamb’s

Chop. It has only recently begun

trending toward the Democrats, but another special election here, in April

2019, put Democrats in striking distance of taking over the state Senate in

2020. Both the top Republican in the

state House, Speaker Mike Turzai (TER-zigh), and its biggest conservative

firebrand, Daryl Metcalf, have districts here, complicating their political

futures. (For what it’s worth, the top

Democrat in the state House, Frank Dermody, represents a Murthaland district in

northeastern Allegheny County that’s trending Republican.)

The

city of Pittsburgh itself, as well as several smaller, minority-dominated

communities to its east and northwest, are as liberal and Democratic as ever,

to the extent that democratic socialists have made inroads in local

politics. In honor of the most prominent

of them, John Fetterman, who parlayed media attention as the mayor of Braddock,

a small mill town, into the lieutenant governorship in 2018, I’m calling the

area the Yinz* Democratic Republic of Fettermania. During the 1970s and 1980s, it was not

unusual for a Republican candidate to carry Allegheny County while losing some

of the surrounding counties; since 2000, Allegheny has become clearly the most

Democratic county in this part of the state.

Pittsburgh, like Philadelphia, was strongly Republican between the Civil

War and the New Deal, began voting Democratic under Franklin Roosevelt, and saw

Democrats take over local government shortly afterward. Allegheny County Democrats have had less

success than their Republican neighbors in winning statewide; after David

Lawrence, a former mayor of Pittsburgh who served as governor from 1959-63,

none has been elected governor or U.S. senator.

The

most nationally known political figure from Allegheny County in recent years is

Pennsylvania’s former senator, Rick Santorum.

Santorum first ran for Congress in a district combining suburban and

industrial areas in 1990, upsetting Democratic incumbent Doug Walgren. The district was reconfigured to have a

three-to-one Democratic majority in 1991, but Santorum was still re-elected

handily, in part because a clown-car primary produced a weak Democratic

opponent. He was elected to the U.S.

Senate in the Republican wave of 1994, served two terms, and was voted out in

the Democratic wave of 2006. His policies

were a combination of staunch social conservatism and populist economic

policies, such as a lukewarm attitude toward free trade and staunch opposition

to illegal immigration. Santorum’s

career seemed to be over until 2012, when he ran as a populist alternative to

Mitt Romney and carried eleven states in the Republican presidential

primary. In both Pennsylvania and

presidential politics, Rick Santorum served as a forerunner to Donald

Trump.

Finally,

Erie County sits at the northwest corner of the state, giving it access

to the Great Lakes. Erie is Pennsylvania’s

fourth-largest city, behind only Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Allentown, and

like many other Pennsylvania cities, it thrived during the industrial era and

has struggled economically in recent decades.

Due to its isolation from other population centers- as the crow flies,

Toronto is closer to Erie than Pittsburgh, and Detroit is closer than

Philadelphia- it is best considered its own entity. Like Scranton at the opposite end of northern

Pennsylvania, Erie was Democratic-leaning, and didn’t show much sign of

changing, until Donald Trump ran in 2016 and became the first Republican

Presidential candidate since 1984 to carry Erie County. Only one Erie County resident has ever held a

major statewide office**: Tom Ridge, who served as governor from

1995-2001. (Outside Pennsylvania, he is

probably best known as the first Secretary of Homeland Security.) Ridge, a pro-choice, moderate Republican who

self-deprecatingly referred to himself as “the man nobody has heard of from the

place nobody has been”, won the 1994 primary for governor over the more

conservative Attorney General Ernie Preate, of Scranton, while Preate was

caught up in scandal and a third candidate, then-state Sen. Mike Fisher, was

splitting the conservative vote. Ridge

went on to win the general election amid that year’s Republican wave and a

split between outgoing governor Bob Casey Sr., a pro-life Democrat, and the

Democratic nominee, Lt. Gov. Mark Singel, over abortion.

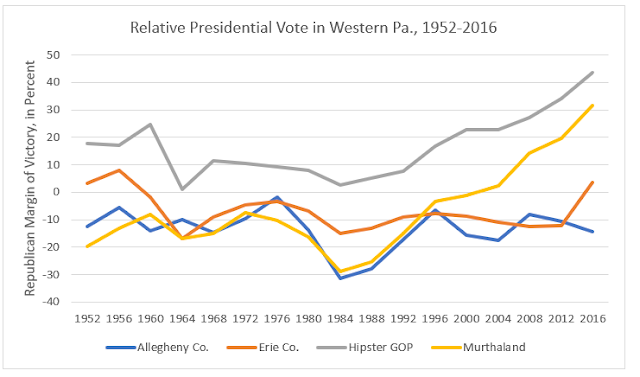

Western

Pennsylvania Political and Demographic Trends

Moderate,

working-class Democrats who occasionally vote Republican are often called

“Reagan Democrats”. However accurate

that might be elsewhere, it’s not correct in western Pennsylvania, where Walter

Mondale won handily in 1984.

For

the purposes of these graphs, I consider Armstrong, Beaver, Cambria, Clinton,

Elk, Fayette, Greene, Indiana, Lawrence, Mercer, Washington, and Westmoreland

counties to be Murthaland, and Butler, Clarion, Clearfield, Crawford, Forest,

Jefferson, Venango, and Warren counties to be the Hipster Republicans. The recession of the early 1980s coincided

with the collapse of the region’s steel industry, hurting Ronald Reagan’s

re-election campaign in the area. In

Western Pennsylvania as a whole, Walter Mondale received about 860,000 votes to

Reagan’s 750,000. Even in the

traditionally Republican counties, Reagan barely performed better than in the

nationwide vote. Since then, Republicans

have surged in the area. In 2004,

Murthaland flipped from Al Gore to George W. Bush, and in 2012, Western

Pennsylvania as a whole flipped from Barack Obama to Mitt Romney; neither has

looked back. The great irony of John

Murtha’s career is that, just as he was becoming nationally known as an

opponent of George W. Bush, his constituents were flocking to Bush’s party.

Allegheny

County closely tracked Murthaland from the 1950s to the 1990s, but after 2000,

as the partisan divide between urban and rural America deepened, the two areas

diverged. The graph also shows why Erie

County’s vote for Donald Trump came as a surprise; before 2016, it had been

reliably Democratic, with Barack Obama doing better there than he did in

Allegheny County. Elsewhere in western

Pennsylvania, Trump merely accelerated existing trends.

To

see how far the Democratic trend is spreading in the Pittsburgh suburbs, let’s

look at Allegheny County and its neighbors.

In Butler County, traditionally the most Republican of the five, the

Republicans appear to be leveling off as the other counties catch up to it. Beaver, Washington, and Westmoreland

counties, though, continue to move to the right of the national

electorate. It may be that, as these

areas become less industrial and rural and more suburban, Democrats will have a

revival here, but there’s no evidence of it in Presidential elections yet.

The

most important demographic trend in western Pennsylvania is its steadily

declining population. Allegheny County

peaked at about 1.6 million people in 1960 and is now just above 1.2

million. Murthaland peaked later, in

1980, but has been falling since. Erie

County grew from 1950 to 1980, but has stagnated since then. The only consistent demographic bright spot is

Butler County, which almost doubled in population between 1950 and 2010,

growing from about 97,000 people to 184,000.

In the mid-twentieth century, Western Pennsylvania was the most populous

of Pennsylvania’s regions. During the

1980s, Southeastern Pennsylvania passed it, and if current trends continue

(with Central Pennsylvania gaining about 200,000 people per decade and Western

Pennsylvania losing about 100,000), Central Pennsylvania will pass it sometime

around 2040.

The

city of Pittsburgh has lost over half its population since 1950. The remainder of Allegheny County grew in the

1950s and 1960s due to the expansion of suburbs, but it has also declined since

then, though not as rapidly as Pittsburgh.

Because of this, as a proportion of the county’s population, Pittsburgh

has declined from forty-five percent in 1950 to about a quarter today. The fact that Allegheny County is trending to

the Democrats while Pittsburgh is shrinking suggests that the trend is mostly

in the suburbs.

*The

Pittsburgh colloquial plural of “you”.

**Raymond

Shafer, from neighboring Crawford County, served as governor from 1967-71.